La Questa de Trujillo

It was spring 2021 and, after having to lay low during the pandemic for most of 2020, it was time for an adventure. I heard the road from Monticello NM up to Springtime Campground north of Vicks Peak in Cibola National Forest was rough and, having been advised against taking my RV up there, I had to go find out for myself.

Checking out the area on various maps I stumbled on a landmark along Forest Road 225, the road up there, called “La Questa de Trujillo“. Well I’ll be...

View from atop La Questa de Trujillo

My interest in this area stems from my friend Billy Trujillo occasionally mentioning how his family was among the first hispanic settlers in Monticello, having come up the Rio Grande with the Conquistadors in the 17th century, and how his grandfather would leave Monticello at 3 or 4 in the morning to make the 17 mile trip up to the Springtime Campground area early enough to cut a load of logs up there before having to head back down off the mountain before dark. And how his grandfather figured out a way to brake the loaded wagon coming down the steep grades, using a stout pole jammed into the ground somehow, so as not to overrun the team.

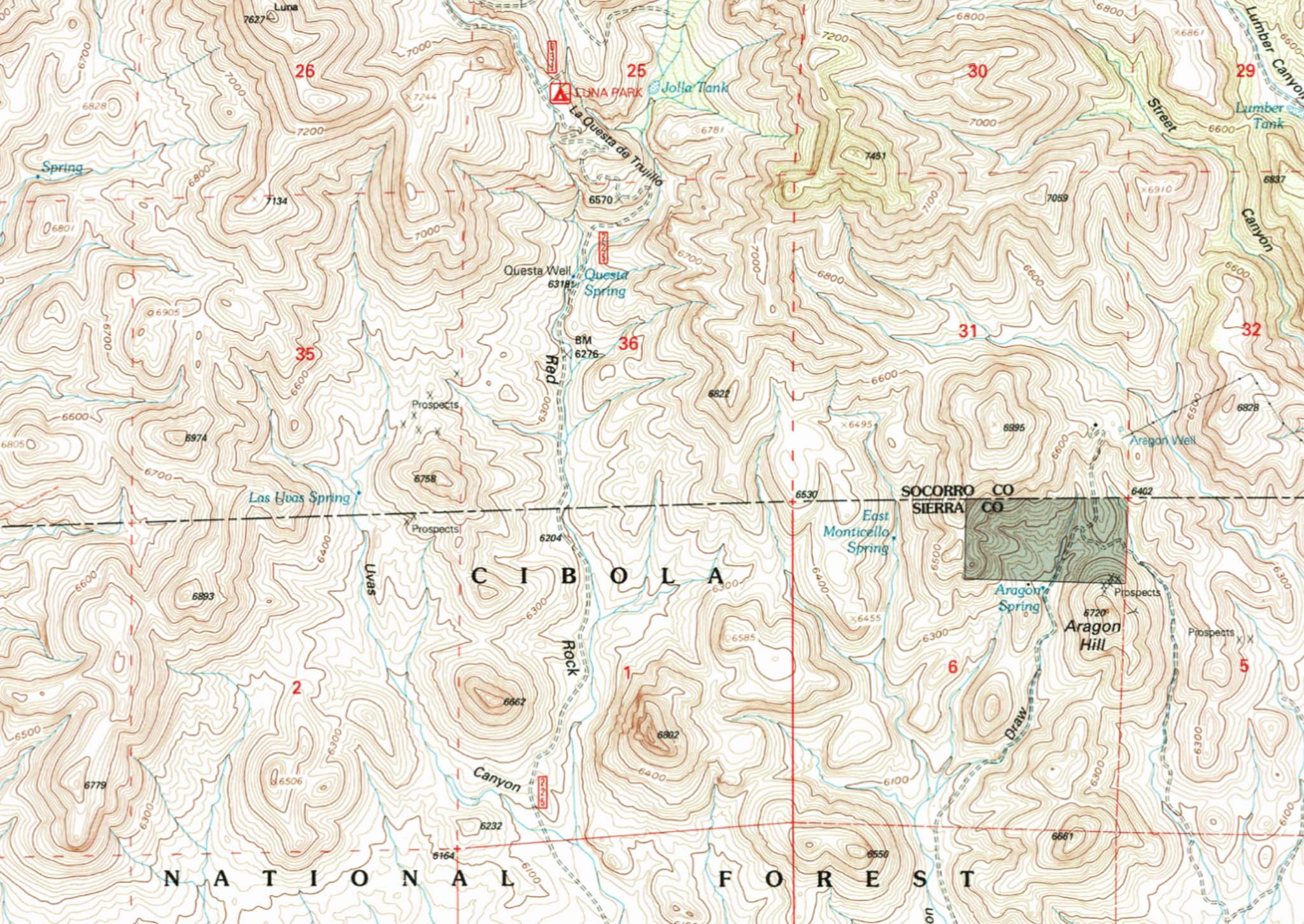

When I found La Questa de Trujillo identified on the map as a particularly steep section of the road, and when I then found “la questa” translated (incorrectly?) to mean “the take-off” in English, I just HAD to check it out.

Putting La Questa de Trujillo on the Map

USGS Monticello NM Topo Map with La Questa de Trujillo

Apparently this steep section of Forest Road 225 with it’s many switchbacks is named after this Trujillo family story. Billy says it was his cousin who had La Questa de Trujillo put on the map. It’s appearance on USGS maps coincides with the Apache Kid Peak designation 13 Nov 1980. Proposed new geographic names can be submitted to the U.S. Board on Geographic Names and perhaps this is how Billy’s cousin got La Questa de Trujillo added to the map.

“Questa” is apparently a corruption of “cuesta”, which means the flank or slope of a hill or sloping ground in Spanish. A cuesta in geology is a hill or ridge with a gentle slope on one side, and a steep slope on the other. Both uses of the word might apply here - it’s a hillside slope and it does descend from a ridge with a steeper slope on the other side.

The Road Up La Questa de Trujillo

Highlighted road up La Questa de Trujillo as seen from below Questa Well

In mid April I took a ride up to Luna Park Campground at the top of La Questa de Trujillo in my RV to explore for a bit before heading on up to check out the Springtime Campground area.

I heard the road would be difficult and it was. The first section of FR 225 leaving Red Rock Road was very rocky and rough but it soon improved and while there were several more rocky spots the road was not too bad the rest of the way up to Luna Park Campground. The road is pretty well maintained with several new culverts and diversions though the surface is graded from native material with nothing added. Where the native material is gravel the surface is gravel as you see above; where the native material is rocky the surface is rocky. The La Questa de Trujillo section is indeed steep with many switchbacks but is mostly gravel. It gains about 400 feet in altitude in half a mile (about 15% avg). That’s pretty steep.

I can easily imagine the challenge of getting a heavily loaded lumber wagon down that grade without mishap and I wonder what the road looked like in the 1900-1910 era I am imagining here, before bulldozers and graders were available to whoever built the road. Building a wagon road through such rocky terrain must have been a bit of a challenge.

Luna Park

Beyond Luna Park Campground the road goes through a short, narrow, canyon that opens onto a nice valley called Luna Park on the maps. Why name it Luna Park? Was the valley settled? I think it was though not extensively. I took a walk about one morning and found what looks to be the foundations of a couple of rude settlers cabins or shepherds cabins in the second arroyo on the left coming into the valley, the one that was dammed to form Luna Park Tank, downstream of the tank (the arroyo was bulldozed to form the tank and the runoff from a third arroyo was channeled into it). There may be other foundations farther up the valley and there is the old Priest Mine shown on the map up at the head of the valley. I didn’t explore that far up; I only walked up about a mile.

An Apache Camp?

View to the southeast from the ridge with rock-ringed wickiup sites on the small plateau just below

Opposite Luna Park Campground is a two-track leading steeply up to a ridge overlooking Luna Park and the Vicks Peak area to the west and down the valley towards Alamosa Canyon and the Rio Grande River to the southeast.

Up there I found a few rock-ringed hut (wickiup) circles and a couple smaller circles on the small plateau on the east side of the ridge. There are several fire rings up there too but most of them seem modern to me. The Apache were quite mobile and made very rude shelters for a short stay at a camp. These were much simpler than the tipis of the plains people and usually all that is left is the circle of rocks they used to anchor these simple brush and blanket shelters (called wickiups).

Figure 3. Fly’s 1886 photograph no. 173, entitled ‘Geronimo’s camp with sentinel’ (taken at Geronimo’s surrender at Cañon de los Embudos, Sonora, Mexico, which occurred on 25-27 March 1886. jhc)

Geronimo's Wickiups

Close inspection of the images shows that these are not ‘jacals’ but rather are huts and that ocotillo branches were also incorporated into some of the wickiup frameworks at Embudos(Figures 1 and 3). Ocotillo, yucca and agave are also shown growing naturally and each is present today, but of these only ocotillo branches are sufficiently supple to bend, as shown in the framework of the wickiup in Figure 1. Some of the ocotillo branches so employed were still rooted and were simply bent over to form one side of the structure, alleviating the need for rock supports and accounting for breaks in rock alignments (Figure 3). In at least two instances the head and leaves of dried agaves and yuccas were used, along with blankets and other fabrics, to make the side walls. Some structures incorporated stiff robust yucca or agave stalks to form conical tipi-like constructions. In most instances, untrimmed poles and branches were incorporated as found, as were other materials at hand.

…

Highly mobile groups in warmer climates and varied physiographic environments (such as the Southwestern basin-and-range province) tend to seek terrain sectors (such as elevated rocky projections and rocky slopes) that facilitate successful improvisation, including shelter construction, while maximising security and other factors.

From: Nineteenth-century Apache wickiups: Historically documented models for archaeological signatures of the dwellings of mobile people by Deni Seymour, March 2009

Billy says the Apaches hid out in the Springtime Campground area, a remote canyon below Vicks Peak (named after Apache chief Victorio) at some point. In late 1877, Geronimo, Victorio, and Nana fled the San Carlos reservation in Arizona with about 200 warriors and spent the next few years raiding in Mexico, Arizona, and New Mexico, including in this area. This ridge would make a good, secure, camp to watch for anyone approaching along the trail to Vicks Peak and I’m guessing this Apache camp dates to that period.

There is also evidence of a small wickiup circle just above a faintly visible dam across the first arroyo on the left coming into the Luna Park valley from the canyon. This could have been a water source for this camp which was just over the ridge to the east.

The Road From Luna Park to Springtime Campground

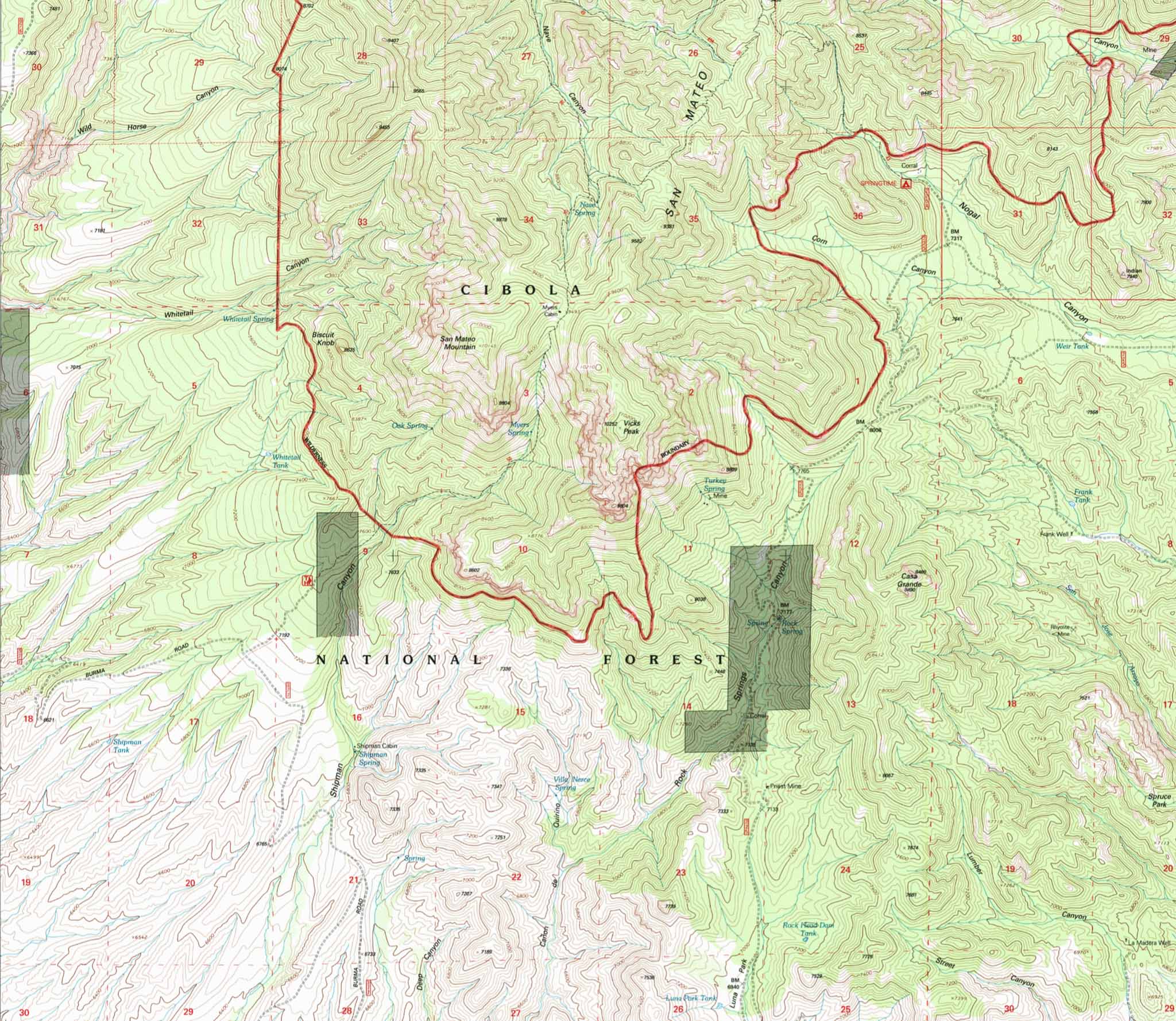

Luna Park and the road to Vicks Peak and Springtime Campground

Holy moly! The 6-7 miles from Luna Park Campground up to Springtime Campground is a quite a challenge with the RV. After the long hill out of the Luna Park valley the road takes a steep descent of several hundred feet down into Rock Springs Canyon and then back up the other side along the southeast flank of Vicks Peak to a pass at 8,000 feet before descending once again to Springtime Campground (at the head of Nogal Canyon) at 7,400 feet. Like the section up to Luna Park, the road is well maintained though very rocky in places and also very, very, steep in places. My RV made it ok but it was pretty rough going in spots.

The road from Luna Park to Springtime Campground on the 1995 USGS Vicks Peak Quadrangle map

This road would be tough enough to build with modern equipment but it’s hard to imagine a wagon road being built all the way up to Springtime Canyon by the early 20th century with the miles of rocks, boulders, arroyos, cliffs, and canyons to deal with. It makes sense there would be a horse trail up to that area used by the Apaches and early settlers and prospectors, but a wagon road? It seems a bit much to me but apparently they built it.

Those tall, straight, Ponderosa Pines up on the mountain must have been valuable!